The missus and I have a ritual – we rewatch Mad Men once a year. By the third go, Jon Hamm and January Jones’ good looks are a little less overwhelming. The characters and writing become familiar, though no less brilliant. What stands out, more and more, is the art design. The bar is high for a period drama- you want everything to be accurate and timeline-correct. But Mad Men takes it to a whole other level with its recreation of the mid-century modern aesthetic of 60’s East Coast homes and offices.

You could pick any random still from the show (like I have above) and marvel at the detailing that’s gone into the design. This is not just for the main elements like couches and tables, but also the accents, the decorative elements, the lighting. It’s all gorgeous. Clean lines, unified themes and complementary colours.

American offices and homes weren’t always so pretty though. It took one company and many, many brilliant minds to will it into creation. This is their story.

We begin in Zeeland, Michigan. The town had been founded in 1847 by Dutch settlers, part of an organised church group. This early sense of community permeated every aspect of daily life, so when the town’s only canning company went bust, they all came together to revive it. The obvious pivot was to making furniture, for two reasons. The nearby town of Grand Rapids was nationally renowned for its prowess, and hopefully some that aura and talent would rub off on Zeeland. The second, and related reason, was that the Dutch had a rich history of furniture making, dating back to the 17th century.1

The new venture, started in 1905, was named the Star Furniture Company, and shares were broadly held amongst the townspeople. The first products were bedroom suites. In 1909, the company made probably its most important hire – Dirk Jan (D.J.) De Pree, fresh out of high school, was tasked with low level administrative work. By 1919, he rose to be president of the little outfit. In 1923, the majority stockholder and GM, Jacob Elbenaas, decided to move to Texas to cash in on the oil boom. D.J. convinced his father-in-law to acquire Elbenaas’ stake, and borrowed some money to buy the rest. D.J became GM of the new company, which was renamed after newly appointed president and D.J.’s father-in-law: Herman Miller.

For the first couple of decades, the company had been playing the game like everyone else. The furniture industry at the time was fragmented and directionless. Dozens of little ventures like Star would churn out the same designs of home furniture pieces every year, which were themselves recycled from the past couple of centuries. Sometimes Louis XVI would be trending, and sometimes it would be the Queen Anne style. But what drove these cycles?

The tastemakers at the time were the salesmen, mercenaries who worked on commission, represented seven or eight factories at once and could make or break a factory’s entire season. After all, they controlled access to the large retailers. Exhibition buildings came up in major furniture markets, and factories were doing up to four collections per year! If they misread the trend, or missed the mark on the pricing, the entire season would be a washout, and they’d have to liquidate the collection at pennies on the dollar.2 These conditions did not allow for innovation, or a feedback loop from the end user to the factory’s inhouse designer. Naturally, factories continued to make what had always worked, and hoped that they got their timing right.

The Grand Rapids area was under a more specific threat- new factories were coming up in the Southern states, closer to lumber sources and (ahem) with much cheaper labour. D.J. didn’t know it, but he was steering his company into the perfect storm. 1929 and the Great Depression rolled around. Sales nosedived, and many stores and factories shuttered. Herman Miller had only one year of runway left.

For the first time, D.J. sat down and took stock of his situation- the treadmill of sales cycles, the lack of scale, the missing connect with the end user. Where the whole world saw an existential threat, D.J. saw an opportunity to course correct. He knew things had to change, and it was the right time to change them. But how?

Before we get to the answer, we should take a moment and consider D.J. De Pree. Born in 1891, a lifelong company man, and now, GM of this little town enterprise. He was 373 when one of his employees, Herman Rummelt, passed away in his sleep. As any GM should, D.J. visited Rummelt’s widow. She took him around the house, and showed him all the lovely little things Rummelt had handcrafted. She brought him a sheaf of papers – his poetry. The pastor later read some of this poetry in Rummelt’s funeral.

This day had a profound impact on D.J. As any manager does, he had mentally abstracted his workers as “resources”, akin to lumber or electricity. A look at Rummelt’s rich personal life and back story tore down that façade. He had an insight that would require you or I a large dose of psychedelics to get to.

“Well, walking home from there, God was dealing with me about this whole thing, the attitude toward working people. I began to realize that we were either all ordinary or all extraordinary. And by the time I reached the front porch of our house, I had concluded that we are all extraordinary. My whole attitude had changed.”

- D.J. De Pree, President, Herman Miller

This tale is a part of company lore. And sure, it has probably been festooned a little with every telling. But in everything I have researched about Herman Miller’s and D.J.’s future journey, this was a pivotal moment for them both. It actually does explain many of his future choices, and the unusual pivots the company made. It also explains D.J.’s response to the 1929 crisis: not panic or despair, but to think deeply about the industry, and his place in it.

That’s the thing about epiphanies: one is never the same again. D. J.’s would set the stage for the creation of the largest furniture company in the world. More importantly, it would demonstrate a new way of doing business - world-changing, path-breaking and yet inclusive and collaborative.

The answer to D.J.’s puzzle literally walked in the door in July, 1930. 36-year-old Gilbert Rohde talked about design philosophy, and wanted $1000 for his bedroom suite design, which D.J. turned down. He was more amenable to Rohde’s royalty suggestion – a 3% commission on every piece sold. This was commonplace enough. What was unusual was the design itself: clean, straight lines, no carvings, mouldings or embellishments of any kind. Pure form following function. Choosing the best material for the job, not just for the sake of appearance.

D.J. didn’t know it, but this was his introduction to modern design. Would he have been so amenable if he hadn’t been rewired in 1927? I don’t think so. Now, however, D.J. bought Rohde’s philosophy even before he bought his designs – that good furniture should recede into the background, not draw attention away from the most important thing in the house- the people. Furniture was enabling, utilitarian and multipurpose. Not an end unto itself but a means for better living. In D.J.’s own words:

Gilbert Rohde elevated our thinking from selling merely furniture to selling a way of life.

- D.J. De Pree, President, Herman Miller

The modern furniture line debuted at the Chicago Century of Progress expo in 1933. I had to mention that as an excuse to share this gorgeous poster:

Rohde’s influence on Herman Miller and D.J. went even further. He pushed for a deeper collaboration between the designer and the production and sales departments. He took it upon himself to influence strategy and direction at the company level too, pushing for more modern lines, even at the expense of the existing business. This was unprecedented- until now designers were contractors who provided designs, and were paid for them. This kind of deep integration would result in unexpected and very profitable outcomes in the years to come.

At Rohde’s urging, Herman Miller discontinued period furniture in 1936. It would now focus only on high quality, modern, original designs – a shift in positioning and brand values. Imagine the courage it takes to jettison your cash cow and jump in an unknown abyss without a safety cord. To emphasize- this wasn’t just a new design language. Modern furniture was intended to last longer, be more multifunctional. It would allow Herman Miller to break out of the “season” trap and develop designs with longer lifecycles – which in turn would allow it to extract more efficiencies with mass production. The company was rewriting its entire DNA, and also that of the entire industry. It is a testament to D.J. De Pree’s faith in the concept and his people, that he took the leap.

In the same vein, Herman Miller opened the first ever manufacturer’s showroom at the Merchandise Mart in Chicago. This wasn’t aimed at buyers from retail stores, but the general public. The company had to increase awareness of the radical new movement they were kickstarting. This was inevitable, because they were facing some headwinds with the industry veterans.

The problem was that architects and decorators didn’t really understand Rohde’s designs. They just didn’t fit into the “curation” mindset that these folks had. One could not pick up one Rohde piece in a living room that was a mishmash of Victorian and Edwardian and God knows what else. The new Herman Miller line was a system of living, and it only worked with itself.

What followed Chicago was a larger, even braver experiment in New York City. A 6000 square foot showroom was opened in 1941. The showroom, as D.J.’s son Hugh describes it, was a mecca of modern design:

Can you imagine over six thousand square feet of fantasy, filled with what was then called modern furniture, in 1941? It was a setting so stunning that the visitor could not even imagine living in such an atmosphere. That was the general first reaction. The second thought was, ‘Wow! Can I have this? Can I live in this kind of space? What does it take? How much is it and when can I have it?”

- Hugh De Pree, President, Herman Miller

There was something else that was new about the New York showroom. For the first time, the customer was not just being foisted with something from the catalogue. The salespeople would try to understand the customer’s unique requirements – window placement, foot traffic and the like- and try to come up with a custom combination of products that offered, for the first time, a solution. This was so radical that the showroom wouldn’t hire anyone with past furniture sales experience. They would already be infected with the old thinking and just couldn’t work with this new approach.

In 1942, Gilbert Rohde brought this philosophy to a whole new market for Herman Miller: office furniture. His Executive Office Group was an unprecedented modular solution for putting together executive offices. It championed using a minimum number of components, to configure personalised workstations. The 15 modules could be combined in more than 400 ways, allowing the user to setup their workspace exactly to their specifications. In 1942! Amazing, and the precursor to many a world changing innovation down the road.

Sadly, Rohde died in 1944, leaving a huge void in both Herman Miller and the design world at large. The changes he set in motion still continue to influence our daily lives nearly a century later, and while he may not have become a household name like many of his successors, they were only able to see so far because they stood on his colossal shoulders.

“The most interesting thing in the home is the people who live there. I’m designing for them.”

- Gilbert Rohde, designer (1894-1944)

While Rohde’s passing left a hole in the company, D.J. was under no pressure to fill it immediately. WWII would rage on for another year, and no new products would be introduced amidst all that uncertainty and supply shortages. Herman Miller’s new direction had resonated with the industry and general public, which meant they were spoilt for choice. Many renowned designers threw their hat in the ring, and the company nearly closed the deal with one.

But again, D.J. listened to his instincts and took a contrarian approach. He had chanced upon an article in Life magazine about George Nelson. Nelson, whose parents owned a drugstore, had attended Yale University. Caught in a thunderstorm, he once sought shelter in Yale’s architecture school, the first he learnt of its existence. Walking through the building and seeing some student exhibits made his life’s pursuit clear- he was going to be an architect. He completed his architecture degree in 1928 and got a second one in fine arts for good measure.

Subsequently awarded the Rome Prize, Nelson lived in Europe for two years, all expenses paid. He took this time to interview many of the pioneers of the Modernist movement for a magazine. His writing work continued even upon returning to the US, as he championed Modernism at the renowned Architectural Forum magazine. In a book he co-authored (Tomorrow’s House, 1945) Nelson introduced two seminal concepts – the family room and the storage wall.

The latter is more relevant for our story, but let’s pause for a second and fully appreciate the former. Nelson was actually defining the family room for the first time: an informal, multi-use room in the house. Before this, from the architect’s perspective every room had a defined purpose, even if it was used otherwise. Staggers the mind to think about it now, but the very contours of modern life were being drawn here. That’s how cutting edge and seminal their work was.

Anyway, back to the storage wall. American homes back then had dead spaces between the drywall, and Nelson asked- “What’s inside the wall?”. The answer was his clever design- the storage wall. This clever design turned dead space between walls into a multipurpose storage unit:

It was this design that D.J. saw featured in Life magazine. And just like that, he chose a man who had never worked on furniture in his life to be the lead designer of Herman Miller. This wasn’t bravado- his decision was rooted in his faith in the principles laid out by Rohde, and his belief in the inevitability of modernism. He knew that it was easier for Nelson to figure out furniture design than for D.J. to infuse modernism in an experienced designer.

Nelson didn’t disappoint. His first collection, unveiled in 1946, was a smash hit. He had somehow designed 70 pieces in a year and a half. But his influence ran far deeper. Nelson took Rohde’s thinking to its logical next stage. He got fully involved in management. He placed the designer at the centre of the organisation- between the factory foreman, the sales head and the CEO. He designed the advertisements, the company literature and the catalogues. Nelson wasn’t just designing for Herman Miller; he was redesigning Herman Miller itself. For the first time, it was truly a design-driven organisation. In fact, his office even redesigned the Herman Miller logo - a powerful metaphor.

During his magazine stint, Nelson had become acquainted with Charles Eames and his seminal 1940 exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). In 1946, Eames invited Nelson to show him some new drawings of chairs made out of moulded plywood. Nelson was stunned- he had been working on something remarkably similar. He urged D.J. to drive down and take a look, and also hire Eames. Interestingly, Eames was also being wooed by arch-rival furniture firm Knoll. In the end, he went with Herman Miller because they treated their people better and had fewer labour issues. Funny how that goes.

It is hard to do justice to Charles and Ray Eames and their legacy3. Charles was awarded the Most Influential Designer of the 20th century by his peers. He was a polymath, dabbling in film, design and architecture with equal flair. He was one of the founding fathers of the modernist movement, and yet wore all these accolades with a charming nonchalance.

I think his brilliance is best illustrated in his description of the humble Indian lota:

“First, shut out all preconceived ideas and begin to consider factor after factor: the optimum amount of liquid to be fetched, carried, poured, and stored in a prescribed set of circumstances; the size, strength, and gender of the hands that would manipulate it, the way it is to be transported—head, hip, hand, back—the centre of gravity when empty, when full; its balance when rotated for pouring; its sculpture as it fits the palm of the hand, the curve of the hip; the relation of opening to volume in terms of storage uses and objects other than liquid; heat transfer; can it be grasped if the liquid is hot; how pleasant does it feel, eyes closed, eyes opened; how does it sound when it strikes another vessel; what is the possible material; what is the cost in terms of working; what is the cost in terms of ultimate service; how will the material affect the contents?”

- Charles Eames, on the Indian lota

He brought this same rigor and first principles thinking to his designs, most notable of which were his chairs. Although he came to be known for a premium product that I’ll introduce shortly, Eames’ best work was in designing mass-produced, low-cost chairs. Just like the lota, he let the material and end use shape the design, not the other way round. You may think you’re unfamiliar with Eames’ work, but his designs are still around to this day.

With that, here’s by far the best discovery I made while researching this piece: The actual, real unveiling of the iconic Eames Lounge chair on national television, by Charles and Ray Eames themselves! God bless the internet.

How many chairs did you recognise in the opening segment? Did you notice the silhouette of the chair before it was unveiled? And the playful touches in the promo video at the end? The Eames’ fingerprints are all over!

Charles’ brilliance comes across in another anecdote that Max De Pree tells, of the time the international licensees came to visit:

It was billed as ‘A Day with Charles Eames.’ We started out in the morning at Twentieth-Century Fox Studios. They had a little champagne, a coffee break, you know. He, of course, had that all set up beautifully. And then we went up to his house for lunch. You walked into the house and looked out to the yard, where he had this big circus tent up. And he had white tables and red and blue chairs, you know. Eames chairs. And he handed out little sunglasses—red, white, and blue stripes. It was just unbelievable.

So then we went down to his studio. Whenever you went to his studio—and I had on a few other occasions to do it—it was always like, oh, you just happened to drop in sort of thing. But there was never a thing left to chance. Anyway, we went through his studio and he showed us all his fastballs in his slow way, and everybody was just overwhelmed. Then he set us down in a little theater and he started to introduce some slide shows. He showed us this marvelous show about his trip to India, and this show and that show.

Then he said, “There’s one more little show that I think you would like to see. The day before I had taken these people to Disneyland. Eames had a photographer or two that he’d put on the bus with me. And Hugh and Max were with us at that point. But anyway, this photographer just took a million pictures of these people at Disneyland. I had had some pictures taken as well, which weren’t too good, even though I hired good people to do it, at the previous stops on the trip. Just as soon as this film would be exposed, I’d send it to Eames.

But all of a sudden this shed that’s his studio just resounded with a stereophonic “Stars and Stripes Forever.” I mean, it just blew the roof off that place. And here on the wall is a three-screen projection going on covering the U.S. trip—including Disneyland—of all these people who were sitting there watching. They had stayed up all night, those Eames people doing those slides. I’m telling you, it was just the most amazing thing. They cried, those licensees. They literally cried.

- Con Boeve, President and CEO, Miltech, a Herman Miller subsidiary

Eames wasn’t the only brilliant designer Nelson brought on board. Alexander Girard, with his keen sense for textiles, colour and designs, brought depth and warmth to the catalogue. Many of his textile and wallpaper designs are still in use today, endlessly knocked off around the world in the last seventy years. Together, Nelson, Eames and Girard were the driving force behind turning Herman Miller from an edgy furniture maker to (in my opinion) one of the most influential firms of the 20th century.

Another notable designer who came on board was Isamo Noguchi4. Although the collaboration didn’t last long, the iconic Noguchi table was the result. Look familiar?

Nelson pushed for more changes, like insisting that the company sell the catalogue instead of giving it away, as was industry practice. In hindsight, this was brilliant- everyone else was pushing merchandise, Herman Miller was offering a way of life. Why should the catalogue be free? That first edition is a collector’s item today, and sells for astonishing sums.

And yet, these collaborations weren’t Nelson’s most significant contribution to the firm. That was just round the corner, as was out next protagonist. But that’ll have to wait until the next chapter.

“Choose your corner, pick away at it carefully, intensely, and to the best of your ability, and that way, you might change the world.”

- Charles Eames

By the 1960’s, George Nelson had successfully transformed Herman Miller. The iconic designs and legendary designers made it a household name. The organisation had settled nicely into its new identity. The home furniture lines still lingered, even though the foray into home fabrics (under Girard) hadn’t panned out. But the writing was on the wall- Herman Miller was largely a chair company. Every internal function was directed towards optimising that vertical. It had created a category and now ruled it. Nice place to be!

But like any good leader, this made D.J De Pree uncomfortable. He understood that over the past decade organisational risk had become concentrated. If anything were to threaten the chair business, it would take the whole company with it. In a move worthy of the best investors, he decided to diversify. But in which direction?

To fully appreciate what followed, we must understand the unique position D.J. and the company were in. This point right here, where a company finally succeeds, also brings with it the seeds of eventual decline. The star product or division swallows the company, inefficiencies set in, and innovation halts. On top of that, D.J. had to contend with the rock star personas of his designers. They were still independent contractors, not employees. Besides, design is a creative pursuit. The company couldn’t compel them to innovate. And through all this there were the comforting growth and profit numbers. A lesser leader would’ve gladly chosen complacency.

But D.J chose Robert Propst. George Nelson had been a left field choice, a designer who had never done furniture before. But Propst was even more unconventional: he was an inventor, not a designer. He’d grown up on a farm, where he and his brother had total freedom to do anything, provided there were no expenses involved. As was the norm then, they were both expected to help around the farm. This curious cocktail of rigorous discipline and unstructured play, combined with Propst’s intellect, led to unexpected outcomes, especially around problem solving.

He joined a university to pursue chemical engineering, but dropped out midway to do a design course. This cross disciplinary journey brought some great insights:

Right in the middle of my undergraduate education I changed to a fine arts major. It’s interesting that maybe that is one of the things that happens to people who get into creative activity—a strange rupture in the midstream of education. You go clear into another department and you find that they don’t believe in any of the things your former department believes in. You stop believing in all disciplines.

- Robert Propst, Inventor

One last piece of the puzzle was missing, and that fell into place when WWII happened, and Propst saw action in the Pacific theater. Here, amidst the chaos and fog of war, he learned true innovation, making do with what was at hand, solving problems on the fly. He came back stateside, got a Master’s degree, taught a little, and then started his own architecture-sculpture consultancy, working with clients as diverse as aircraft component manufacturers, lumber companies and construction companies. It was at this curious juncture that he came up on D.J. and his son Hugh’s radar.

Immediately, D.J sensed a whiff of genius around him, like he had seen earlier with Rohde, Nelson, Eames and Girard. D.J. knew he had to get Propst on board. But he had to do it without rocking the boat. This association started tenuously, with a part time engagement starting in 1958. In a couple of years, both D.J and Propst were ready for a deeper association. The outcome, whether on purpose or not, turned out to be close to what Lockheed Martin had pioneered- a Skunk Works.

In September 1960, Herman Miller announced the formation of a new research division, to be headed by Propst. This was located in Ann Arbor, about 150 miles away from the parent company. To keep from ruffling any feathers, Propst’s mandate was to design anything except furniture itself, which would continue to be under the mother ship and its all-star panel. Imagine that- an unencumbered genius with a reasonable budget and an open mandate. The sky was the limit!

The proceedings began with thirty-two projects, everything from a waffle spring, a roof system, an energy clamp, a heart valve, a squash ball caster, a livestock identification program, to a laser projector. And this was where they started. Curiously, one of the thirty-two projects was an internal requirement.

The division’s new office had been designed and put together using Herman Miller’s own Comprehensive Storage System. But there was a problem. Propst hated it. He approached the problem from first principles, consulted with behavioural psychologists, architects, mathematicians and anthropologists. Instead of just designing furniture, he reframed the problem thus: a system that enabled people to work more effectively and efficiently, while maintaining health, interest and joy in working.

This design study was incorporated into an interior system, which he called Action Office. They even went so far as building prototypes and using them in the new Ann Arbor office. Here, finally, the idea was ripe enough for the mothership. It was assigned to George Nelson and Propst went back to his other exciting projects.

We’ll come back to Action Office in a bit.

An anecdote from Herman Miller’s lore personifies Propst perfectly: during a brief hospitalisation, he thought up a furniture system purpose designed for use in healthcare settings. It would be ten years, and many advances in material science, before Herman Miller could actually bring his designs to life – the Coherent Structures (or Co/Struc) System.

Interestingly, Charles Eames had faced the same issue when he designed his first plastic chair. He had to put development on hold on experiment with other materials while he waited for the plastic technology to catch up with this design. And since I’m such an Eames fanboy, I have to mention: Herman Miller went public in 1970. Guess who designed the gorgeous stock certificate?

But back to Propst. For two years, he lived the dream of every inventor, creating in a vacuum without any commercial pressures. But by 1962, Herman Miller had to pull in the reins. His brilliance was too diverse, too cross disciplinary for them to commercialize every idea. They knew they had to pare down the number of projects to do justice to any of them. There was another issue: resentment had started to creep in at the mothership, for the open mandate and resources the Research Division was pulling in. The focus of the division was narrowed, and collaboration with the mothership increased. So great, however, was the power of some ideas created in that interim, that they would define the company for decades to come.

By 1964, Nelson had created Action Office, a hybrid of Propst’s study and the existing Comprehensive Storage System line. Even though Nelson won the famed Alcoa award for it, the line was not a commercial success. More pertinent, Propst hated it. He felt the principles that he had espoused had been lost in translation. Besides, Action Office I, as it came to be known, was targeted towards executives, not the new multitudes of everyday office workers. The middle management layer of corporate America needed a more customised solution.

After various twists and turns and lots of drama, the Action Office II was introduced in 1968. The system that Propst designed would become the precursor to the most dreaded, soul-crushing symbol of modern corporate life- the cubicle. It would finally push Herman Miller past the Billion-dollar sales mark and come to define offices for generations to come. It would spawn Dilbert, and Office Space, personifying the absurdity of corporate life.

To be fair, the broader idea of an open office plan was already bubbling up in the industry. Also to be fair to Propst, it was corporate America that took his thoughtful, well designed and well-intentioned idea to a bizarre extreme, as only America can.

As a consultant to Herman Miller, the office furniture maker, Mr. Propst championed his pioneering Action Office as a way, he says now, to ''give knowledge workers a more flexible, fluid environment than the rat-maze boxes of offices.''

His concept got lost as companies embraced open-plan offices mainly as a cost saving tactic, laments Mr. Propst, 76, a consultant in suburban Seattle. ''The cubiclizing of people in modern corporations is monolithic insanity,''

- Robert Propst, Inventor. Source

It is a testament to Propst’s particular genius, that the company saw the sun set on its collaborations with the most iconic designers of the century, while managing to reinvent its identity, go public, see a leadership change (from D.J to Max De Pree), and still emerge at the top of its game.

Propst passed away in 2000, but his thinking is no less relevant today:

"Because we can now generate, project and multiply information with ease, we are facing a crisis in quality. We have more but is it worth investing our involvement?"

- Robert Propst, “The Office, a Facility Based on Change", 1968

Herman Miller’s story came round full circle when it cracked the cubicle. As Joseph Shwartz, then VP(Marketing) for Action Office II remarked:

“We are selling all these workstations and we are losing all the chairs. We don’t have a darned chair to sell with an AO station. We will sell a guy 1,000 workstations and he’ll buy 3,000 chairs from Steelcase or from Knoll or somebody else… The plastic chairs are too small, too hard. The soft pads are not appropriate, and they are too expensive… We need some office chairs.”

There it was. Once again, Herman Miller was tempting fate and risked losing its identity by becoming a chair company. But that came much later. For now, Shwartz had made this remark to a designer called Bill Stumpf. Like much of the design talent at the company, Stumpf had charted an unusual course in getting here.

Stumpf’s father died when he was 13, and he was raised by his mother- a gerontology nurse5. After a stint in the Navy and a Bachelors in environmental design, he pursued a Masters from University of Wisconsin-Madison. This was a pivotal time in his life. He found present day design constrictive, that it “denies the human spirit” and led to offices that were “hermetically sealed in artificial space”. His design philosophy and teaching years were centred around restoring human dignity. In his own words:

“Everything was about freeing up the body, designing away constraints.”

- Bill Stumpf, Designer

To this end, while at university, Stumpf worked with orthopaedic and vascular specialists. His research was focussed around the ways people sit. He was thus a perfect fit for Herman Miller. He was also the right person to solve Shwartz’s chair conundrum: one half of the modern office had been perfected, but the other still remained. Stumpf’s response was the Ergon chair: the first purpose built, research backed, ergonomic (hence the name) office chair.

Seems unthinkable today, but before this no one had really thought to pursue this line of enquiry. The context mattered too. This was the first time that vast numbers of people joining the workforce were confined to their desks, using word processors, telephones and (eventually) desktop computers to get things done. Just as the Action Office II seemed inevitable in hindsight, so too was the Ergon chair and the principles it espoused.

Like rewatching Citizen Kane or Seven Samurai in the present day, one might wonder what all the hype is. But it is important to remember that these familiar tropes and visual guides- the entire language of modern storytelling- was born here. So it is with many of the products we’ve looked at so far. But none is more underrated, in my opinion, than the Ergon. The cubicle’s story has been told many times over, but the Ergon shaped our work environment just as much, if not more.

Another designer, Don Chadwick, had also crafted an icon for Herman Miller around the same time: the Chadwick Modular Seating System. A clever sectional design, it allowed for offices and lobbies to have infinite customisation and a pop of colour that captured the zeitgeist of the 70’s perfectly.

In 1984, Herman Miller launched the Equa chair, a collaboration between Stumpf and Chadwick. A unique glass reinforced polyester resin design; it was the first step that the duo took away from upholstered chairs.

Hard plastic, seat pad optional, this was a brave step into uncharted territory- could people be comfortably seated for hours on end without foam? Here’s a reddit comment from someone who seems to agree after decades of use:

It is a testament to Stumpf’s talent that Ethospace, the modular office furniture system he designed with Jack Kelley, is usually a footnote in any story about him. And yet, this was the first time that a steel frame and interchangeable tiles were introduced. You know, the familiar office partitions still used today:

Propst’s Co/Struc system had taken Herman Miller into healthcare settings. Here, it saw an adjacent opportunity. The La-Z-Boy recliner, another homegrown Michigan product, had been around for half a century. It too had become a cultural icon, and a fixture in many American homes. Increasingly, it was being used in healthcare, both residential and hospital environments, as the most convenient option for senior citizens. For those undergoing dialysis or just spending long post-retirement hours in front of the TV, it was soft, comfortable and allowed one to stretch out and rest their legs.

Stumpf and Chadwick, however, saw that the La-Z-Boy was ill suited for this use case. It was not ergonomically designed with senior citizens in mind. Getting into the chair meant the user would have to plop in backwards – not the most elegant solution. The recliner lever was not the easiest to operate. Worst of all, the foam and vinyl upholstery would trap heat and moisture in. Over hours and hours of use this increased the risk of bed sores.

With all these constraints in mind, the duo came up with the Sarah chair. Part of a larger study called Metaforms6, it solved all the problems that they had encountered. The footrest folded away when not in use. Fully reclined, fins supported the calves. Instead of a lever, the recline mechanism was controlled with elegant buttons.

Most important of all: the foam padding wasn’t enclosed in a wooden box, but held in a span of plastic netting that stretched across the frame. The design was thus open on one end and allowed for much thinner sections of foam. Combined, they worked beautifully to dissipate heat. No more sores!

Here, for the first time, we see hairline fractures appear in management’s conviction and support of its designers. They balked at the Sarah’s design, not willing to invest huge sums on an unknown product in an untested market. Where does one even sell high end chairs for senior citizens? Most importantly, why shift focus and resources away from the cash cow- office furniture? Herman Miller was listed now, remember. And this was the 80’s- the heyday of corporate raiders. Not the best time to attempt moonshots that could leave the company vulnerable to hostile takeovers.

The project was canned. Stumpf and Chadwick did not take the rejection lightly, and drifted away from the organisation, working on outside projects. When Herman Miller eventually reached out again and asked the duo if there was anything else they would like to work on, they set forth very clear conditions for their return. They would report directly to the executive board, and no one else. The company acquiesced.

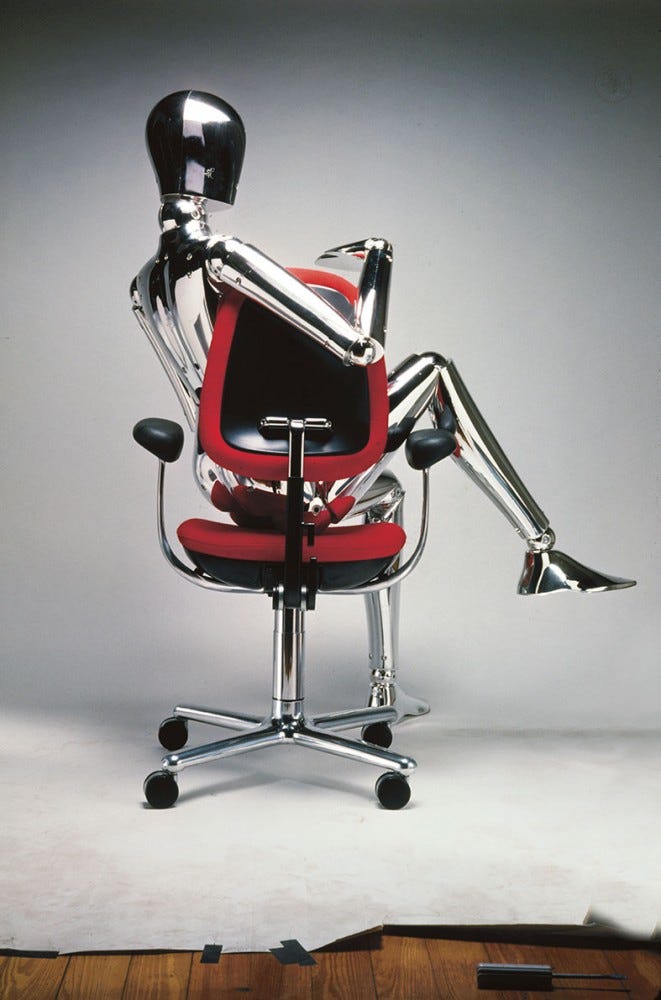

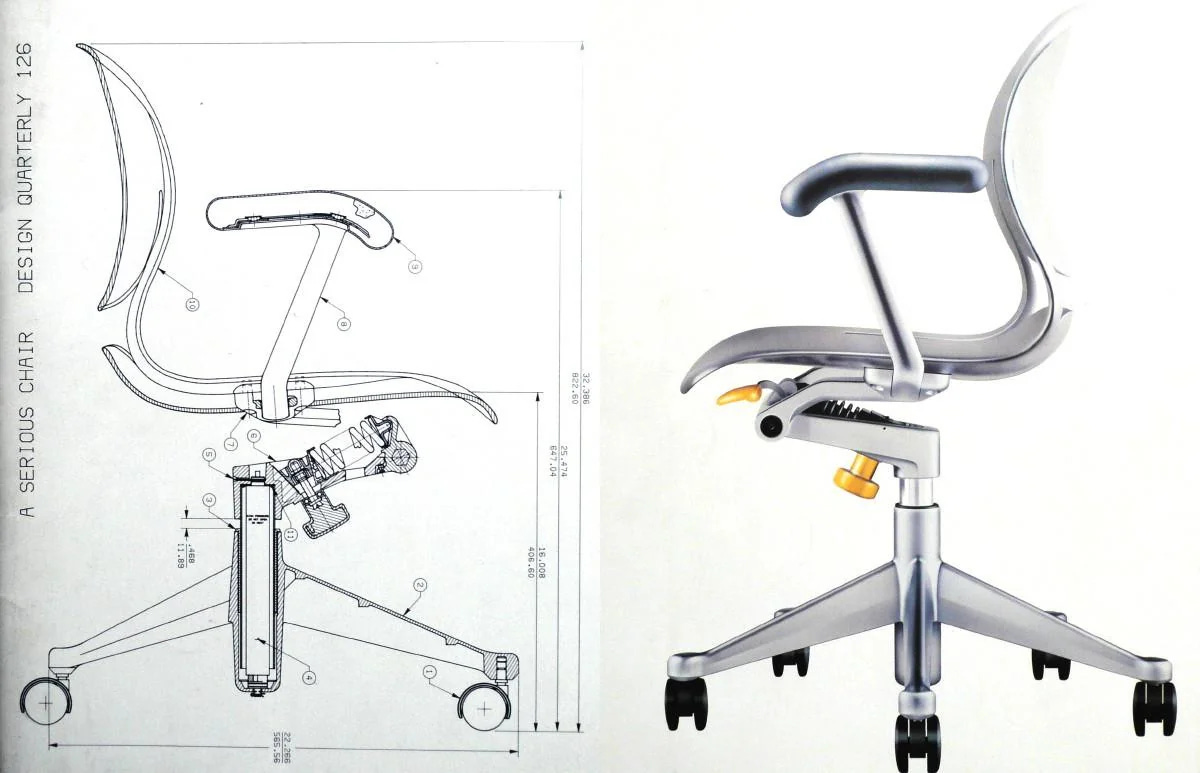

On their terms, they took a relook at the company’s main product line- the office chair. Since they designed the Equa, customers had completed the transition into being full time keyboard warriors. The duo understood that they would need to approach this new behaviour from first principles. Like the Equa, they brought their respective strengths to this new project: Stumpf’s deep understanding of the human form and habits, and Chadwick’s intuitive form-follows-function design sense. From the wreckage of the Metaforms project, they salvaged the synthetic mesh and the recline mechanism. It all came together to form something the world had never seen before: the Aeron chair.

An instant classic, it was inducted into the Museum of Modern Art’s permanent collection even before its launch. And yet, sceptics inside the company lobbied hard against this weird, alien looking thing. The tooling costs were huge, and capital outlays had to begin before the soft materials were even finalised or tested. The CEO, Richard Ruch, finally committed the necessary resources after much deliberation. This may be obvious in hindsight, but it couldn’t have been an easy decision. As Stumpf’s NY Times obit said:

“People forget how controversial it was, how shocking it was, when it first came out,” said Michael Bierut, a partner at Pentagram, the international design company, and a juror for the National Design Awards. The traditional executive chair was lushly upholstered, often with leather.

“The idea was that upholstery equaled comfort,” Mr. Bierut said. “Mr. Stumpf and Mr. Chadwick discovered that comfort could be rendered in a delicate and precise and beautifully engineered way that had nothing to do with creating a throne, but with creating a perfectly calibrated machine for seating.”

Pellicle, which is what the synthetic weave was called, debuted on the Aeron. It is quite likely that a majority of the chairs you’ve sat in during the past decade had some sort of mesh backing. They all trace their lineage to the Aeron – which debuted as recently as 1994! The Aeron launched at a curious time, just at the start of the dotcom bubble in the US. It soon became a standard fixture in the office of any well-funded (or newly listed) tech startup. And as optimism turned to hubris and the bubble finally popped, the Aeron became a symbol of dotcom excess: expensive chairs bought by reckless CEO’s for clueless employees.

Functionally though, the Aeron performed flawlessly. And with its fame, it provided a much-needed push to Herman Miller’s finances. Always a premium product with excellent margins, it helped the company enter the new millennium with full coffers and a deep catalogue of hits. Along the way though, the strain of being listed and the whiplash of riding the bubble had taken its toll, most notably on the leadership and strategy of the company.

But that’s for our next and final instalment!

“True comfort is the absence of awareness. When a chair is a perfect fit for your body, it becomes ‘invisible’ and you’re not aware of it at all.”

- Bill Stumpf

We’ve followed Herman Miller’s journey for nearly a century. In fact, here’s a beautiful video that the company commissioned in 2013, to mark 108 years in 108 seconds. Watch it, for a quick and pretty revision of everything we’ve covered so far.

Notice something odd? A 2013 video, but the last featured product was launched in 1994, almost 20 years earlier. What gives?

Before we answer that, let’s rewind. Remember this amazing quote from D.J De Pree after Rummelt’s funeral?

“Well, walking home from there, God was dealing with me about this whole thing, the attitude toward working people. I began to realize that we were either all ordinary or all extraordinary. And by the time I reached the front porch of our house, I had concluded that we are all extraordinary. My whole attitude had changed.”

- D.J. De Pree, President, Herman Miller

Already, D.J was primed to be more open minded about how he approached the organisational structure and ethos of his company. And yes, first Rohde and then Nelson challenged the way things were done internally. But there was another person who helped rebuild and redesign the organisation in a way that had never been done before. I’ve saved that encounter for last.

In October 1949, D.J and Hugh De Pree attended a meeting sponsored by the Grand Rapids Furniture Manufacturers Association. The speaker’s topic was “Enterprise for Everybody”. In his talk, Dr. Carl Frost spoke about a new, collaborative way of approaching organisational design and functioning. He struck a chord, and the duo soon visited him at Michigan State University, where he taught. Would Dr. Frost help them implement the Scanlon plan at Herman Miller?

The first Scanlon Plan was instituted by Joseph N Scanlon at the steel mill where he was union president. The mill, battered by the Great Depression, was in no position to increase wages as the workers demanded. Scanlon’s idea was to foster innovation by increasing collaboration between the workers and management. He did this by setting up joint committees of the two.

Seems like common sense now, but this was the 1930’s. Back then, management issued commandments from up high, and they were to be followed without question by the workers. This crucial new feedback loop worked both ways, with management being more aware of ground realities, and workers more aligned with longer term organisational goals. The results were spectacular, with more productivity gains and lower friction between management and labour. Scanlon rose to Acting Director of the Steelworkers International Research Department. His ideas were adopted by many industries in the mad scramble for ramping up production during WWII. Sadly, after the war, most managements wanted to go back to the old style of working. Scanlon quit, and joined MIT as a Lecturer. It is here that he perfected his philosophy, and also where the term Scanlon Plan was accidentally coined. From Wikipedia:

There were two conferences going on at MIT and signs were needed to guide attendees. Thus those headed to Scanlon's event were directed to the Scanlon Plan and the name stuck.

Curiously, the first iteration of the Plan did not include a bonus. This made sense, because the very first inductees were companies on the brink of extinction. Even later, Scanlon felt that the mere opportunity to have a larger say in the company was motivation enough for labour to participate. Mercifully, he soon saw the light and developed a participatory bonus plan that ensured incentives were aligned for everyone.

Scanlon’s work with various companies was soon featured in Life, Fortune and other eminent magazines. Time even called him the most sought-after consultant of his time. Two of his colleagues carried on his work – Fred Lesieur and Dr. Carl Frost. Dr. Frost moved from MIT to Michigan State where he expanded on the Scanlon Plan to develop the Frost/Scanlon Principles of Identity, Participation, Equity and Competence. It’s here that his story intersected with the De Prees.

But Dr. Frost wasn’t immediately welcoming and enthusiastic about Herman Miller’s adoption of his principles. In fact, he sent D.J back from that meeting with some deep questions- was he willing to be completely transparent about the inner workings and margins of the company with all his employees? Would he truly be open to ideas and suggestions regardless of where they came from? Dr. Frost had probably seen many managements talk the talk but fail to walk the walk. And the thing with the Scanlon Plan was that it wouldn’t work in half measures.

As their discussions continued, Dr. Frost visited the Zeeland factory and spoke to employees at various levels. Finally, he agreed to install the Plan at Herman Miller. Why did D.J agree? Wasn’t he betting the company again, and that too at a time when it was already on an exponential upward trajectory? That was the genius of D.J De Pree. Just like he glimpsed the future when he first saw Rohde’s designs, he felt the same inevitability about Dr. Frost’s philosophy. This was the future, and D.J would remove all obstacles from Herman Miller’s path in getting there. It also struck a chord with who he was as a person- every single one of his employees was extraordinary. It was only natural, then, that they have a say in the direction of the company and, equally, benefit from its successes.

Thus, Herman Miller’s four principles: Trust, Stewardship, Equity and Innovation. And Herman Miller didn’t just put these up on a board somewhere and forgot about them, only to be mentioned in CEO speeches and annual retreats. They lived them, in every small and big way, leading to nearly a century of world changing innovations. But it wasn’t an easy transition. The company had already been around for decades, and organisational inertia is a powerful force.

One big hurdle was moving from a “per piece” payment of line workers to a more collaborative structure. It took some time for the realisation to dawn that it was much more productive (and lucrative) to work together than to focus on just one’s own output. The committees were another challenge. In explaining management problems to production folks, management learned better ways of clarifying goals, setting benchmarks and prioritising targets. Basically, they learned to manage better.

Good faith from management was rewarded in kind by labour. For instance, while fixing salaries, management fixed as base pay a rough average of what that worker had taken home in the past year or so. But there was an issue- many workers would routinely take home IOU’s from the company, a way of deferring pay for a rainy day, when their numbers lagged or they just couldn’t come in. Should these be counted in deciding the new salary? D.J decided to leave it to each worker. Some brought in all their chits, some brought a few. Many brought none. Imagine that!

Another unique feature of the new Herman Miller was that anyone could make suggestions that had to be deliberated upon by the committees. In the first ten years, the company averaged one suggestion per person per year. Sounds small, but there were about 120 employees then. That meant nearly one new suggestion every three days!

This was the supporting wireframe that helped attract and retain all those rockstar designers. Remember, Eames would’ve gone with Knoll if not for their labour issues. Not only that, it made the organisation nimbler, and open to change. I cannot stress how difficult that is in manufacturing organisations. And then add the egos and idiosyncrasies of celebrity designers, coupled with (down the line) shareholder pressures. It truly is a feat, what D.J pulled off and Max and Hugh nurtured.

In 1977, when it was felt that the Scanlon plan needed to be overhauled, all 2500 hundred employees had a say, by secret ballot, on the need for and extent of the changes. A new set of committees was formed to take inputs and draft the new plan. Again, the final plan was put to a companywide vote for approval. 96% voted in favour. The new Scanlon plan was approved. Quietly, a listed company overhauled its inner workings, bringing everyone into the fold without alienating shareholders.

Fast forward to the late 80’s, corporate raiders were using easy debt to buy out and break up weak companies, more valuable dead than alive, or together than alone. The board of every struggling legacy company hastily passed “golden parachute” plans, ensuring that the executives got handsome pay outs in case their company was acquired and they were laid off. Is it surprising that Herman Miller passed a “silver parachute” program instead? Every single employee- not just management- would get a solid payoff in case the company was acquired and they were laid off, or their pay reduced. This was no accident, but the natural outcome of recognising that everyone is extraordinary.

The company successfully brought in an outside CEO- J. Kermit Campbell from the Dow Corporation, in 1992. Max De Pree retired from the board in 1995, and Campbell became Chairman. Brian Walker, who spent a total of 29 years at Herman Miller, was CEO from 2004 to 2018. He was succeeded by this tone deaf lady:

Does it surprise you, then, that Glassdoor reviews of the company today read like this:

Yeah, sure, the company is an acquisition machine now, swallowing up furniture companies big and small- including in 2021, it’s century old rival Knoll, Inc to become the largest furniture company in the world. It’s even rebranded itself to MillerKnoll. But at its core, it is an enterprise coasting on its past glory, failing to understand the drivers of its former successes.

Herman Miller was known for half a century as being a great place to work- one where every employee was truly valued and heard. What does it say when the CEO couldn’t even offer employees reassurance during a global pandemic, instead pushing for numbers like a Byju’s sales head? Here, then, is the reason I spent countless hours chronicling this company. It is the perfect metaphor for the public corporation- what once was great and true, and has now been corrupted beyond recognition.

I’d also like to emphasize that this isn’t nostalgia or bleeding heart sentiment. Ask yourself, is the present MillerKnoll capable of attracting a Charles Eames? Would shareholders allow a silver parachute plan today? Without the culture that fostered it, there wouldn’t be an Aeron. Or Co/Struc. Or Action Office. Or the Lounge Chair. Or any of the thousand icons that MillerKnoll continues to peddle. New designs rarely hit the mark, and it is just another furniture company, albeit one with a rich catalogue of past hits to mooch off of.

Sales are great though: $3.6B for the year ended June 1, 2024. According to this site, the CEO made nearly $9m in total compensation that year, while the company’s median salary was $64k.

The first responsibility of a leader is to define reality. The last is to say thank you. In between, the leader is a servant.

- Max De Pree

End of the line, folks! I hope you enjoyed reading this series even half as much as I enjoyed researching and writing it. I will never look at furniture the same way again! Do let me know if you’d like more deep dives like this one. Even better if you have company/industry suggestions.

This post, and any analysis I’ve offered, is not investing (or life) advice. It is only my personal opinion. I may hold positions in any of the securities discussed. Do your own due diligence. Don’t depend on random newsletters from internet strangers to make portfolio decisions.

Subscribe, if you like what you see! And remember, either we’re all ordinary, or we’re all extraordinary.

The Dutch were a colonial power in the times of wooden ships: woodworking is bound to be a core strength.

One can’t help but see the echoes with today’s fast fashion brands.

This would come back later in the design of the Sarah chair.

You know who else worked on the Metaforms project? An unknown engineer called James Dyson

Enjoyed the piece. I got some LVMH vibes. Strong designers’ say, new category creation, continuous evolution, same threat of leveraged buyouts. And looking ahead it makes me wonder about the show Severance.

The narrative made it easy to follow the breadth of information. There were multiple jumping-off points and it must have required restraint to not go off on all those tangents.

So apt that I'm sitting on an Aeron chair and typing this xD

wow, wow! that was such an engaging read! thank you!