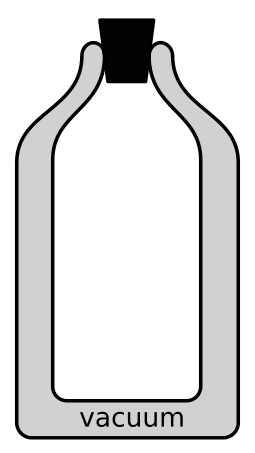

James Dewar invented the vacuum flask in 1892. The design was genius – two flasks, one within the other, joined at the neck. The air between the two flasks was evacuated, creating a vacuum. This vacuum served as insulation, and the palladium that he was experimenting on retained its temperature much longer. Dewar, however, didn’t think his innovation would find much use outside his laboratory and the world of cryogenics. He didn’t file for a patent.

While the original design had been made of brass, two German glassblowers fashioned a smaller flask out of glass. They found that the vacuum worked perfectly – keeping warm drinks warm and cold drinks cold. After a crowdsourcing contest, they settled on a brand name for their flask – Thermos. They were granted a German patent in 1903 and the trademark in 1904.1

As this was the first brand to each the wider market, “Thermos” became synonymous with vacuum flasks for everyday use. The company happily encouraged this usage – it was free publicity estimated in 1917 to be worth $3-4 million dollars a year in the US market alone.2

Around the same time that the Thermos innovation was happening, William Stanley Jr was working as a consultant at General Electric (Yup, that GE). His previous venture, where he had been manufacturing electric transformers, had wound up at GE in 1903 through a series of acquisitions. The factory had been closed in 1907 after a round of corporate consolidation. During research, Stanley found a method to replicate the vacuum flask design using only steel. Until now, glass had been used in mass manufacture of vacuum bottles.

From William Stanley Lighted a Town and Powered an Industry by Bernard A. Drew and Gerard Chapman:

Stanley’s earlier experiences with nickel-plating and with evacuating air from light bulbs found new use here. His bottle required an innovative welding process and the creation of a small vacuum between two metal shells.

In cooperation with engineers at GE, he came up with an electro-welding and immersion process which rendered reliable, invisible, leak-proof welded seams.

Stanley’s product, patented in 1913, lacked the glass core common to the Thermos bottle. The inventor instead used metal. He envisioned, and his company was soon making, a wide variety of liquid and food containers under the Ferrostat, and later Supervac, label.

Stanley’s steel construction exponentially increased use cases for the flask – from the rough and tumble of construction sites to military applications, it could be carried anywhere without fear of breaking. Another extract from William Stanley Lighted a Town:

During World War 1, the Army tested the bottles by tossing samples from soaring airplanes and running over them with heavy field equipment.

In 1923, the Commerce Department also reported that Arabian Sheiks used the bottles in the desert. “All the Better Caravans Include Great Barrington Equipment - American Bottles Considered Superior” bragged a local newspaper headline.

Incredibly, WWII bomber pilots carried Stanley bottles on missions.

Stanley raised funding for his new venture from William H Walker, who eventually bought him out. After Walker’s death in 1917, the business was acquired by a Connecticut firm, Landers, Frary & Clark. They marketed the innovation under their “Universal” brand name.

In 1965, the company was acquired by Aladdin Industries of Tennessee. Aladdin had started out in 1908, making mantle lamps (hence the Aladdin connection)

Aladdin’s big breakthrough had been lunchboxes with licensed characters, including Superman and Mickey Mouse. They had a vacuum flask division too, and the acquisition of Stanley made perfect sense. By now (the mid 60’s), Stanley had become the dependable workhorse of blue-collar workers and campers. A no-frills, no-nonsense flask that could take a fair bit of wear and still last a lifetime. Design and colours were just not a consideration. The category was considered a pure utility.

Sales chugged along, until 2002, when the combined entity was acquired by Seattle-based Pacific Market International (PMI). PMI expanded the brand outside its core vacuum offering, with new lines like barware. It also moved production to China.

And now, we finally arrive at the point of today’s history lesson. In 2016, Stanley introduced the Adventure Quencher tumbler. Here’s what it looks like:

Ashlee LeSueur, a suburban mom in her late 30’s loved using the tumbler. It was even her go-to gifting option. As she tells it, every one of her friends loved it too. Later, Ashlee cofounded a new website/Instagram page with her sister Taylor Cannon and friend Linley Hutchinson. They called it The Buy Guide, and it was a curated selection of products that they either drop-shipped or did affiliate marketing for.3

Naturally, the Stanley cup was one of their first recommendations. It sold out immediately whenever they would recommend it. They were devastated to hear then, in 2019, that the company was withdrawing the product due to poor sales. Somehow, they managed to connect with Lauren Solomon, a national sales manager at Stanley.

The ladies convinced Solomon to accept a 5000-unit PO from them. This was a bold move. The mom demographic was uncharted territory for the brand. Stanley was known as an everyday workhorse and camping/hunting accessory, not a cool lifestyle symbol. Hell, they didn’t even offer the trademark pastel colours that the cup is now known for. Just the staid solids of the parent brand.

Her bet paid off though – the consignment sold out in 5 days. A follow on PO was similarly cleaned out. In January 2020, the Buy Guide founders met the CEO of PMI at the company headquarters. As Ashlee tells it, there was some trepidation to engage with “these blogger girls”. They had some fantastic suggestions for the CEO though – like upping their e-commerce game, embracing affiliate marketing, and offering more colours.

“We promise you; it will sell. We will introduce this cup to an army of other influencers on Instagram, and it will blow your mind what women selling to women looks like,” she added.

-Ms. Ashlee LeSueur, co-founder, The Buy Guide

The company relented, and the product was saved from extinction. Also in 2020, they brought on board Terence Reilly as its president. Reilly was coming in hot after engineering a miraculous turnaround at Crocs, the footwear brand. No stranger to the influencer-hyped, limited-edition game, Reilly embraced the Buy Guide founders’ suggestions and approach whole-heartedly. After all, how often do you get to reinvent a 100-year-old brand?

What was the appeal though? Wasn’t it just a tumbler?

It was desirable to the mom demographic- it signalled an eco-conscious, health positive coolness to their peers. The colours were soothing pastel shades - very Instagram friendly. Their favourite influencers were using it constantly in reels and posts. It was a status symbol - a marker of an elevated, with-it lifestyle. And it was just 50 bucks! (If you could find it).

Sales zoomed, from a staid $70 million a year in 2019 to $400 million in 2022, largely on the back of the Adventure Quencher tumbler. New colours, limited editions and brand collaborations kept the brand fresh and desirable. In fact, many large retailers limited how many tumblers you could buy at once, to prevent feeding into a thriving secondary market. There were early morning queues on days when new colour drops happened. This was priceless publicity – like Thermos a century back. And it was all free.

Another inflection point happened in November 2023. Danielle Lettering posted a video on TikTok. Her car had caught fire and was burnt beyond recognition. But in the cupholder, her Stanley cup was relatively unharmed. And when she shook it, the ice cubes were still intact.

The video went viral. Not one to miss an easy shot, Reilly offered Danielle a replacement cup – and a car to go with it. Sales for 2023 were upwards of $750 million, helped, no doubt, by that fantastic testimonial of its quality.

Where does the brand stand in 2024? It’s still desirable, though the virality has gone down. The rising tide of sales has helped the entire Stanley line-up, even its legacy products. Sales of those classics doubled from 2023 to 2024. Sure, there are competitors, and knock offs. There are ecological and health concerns too. At some point, they are going to saturate the market. And who knows, the fad might shift even before that. But still, even if for a brief moment, a century old utilitarian brand became the personification of cool. And found a whole new audience.

Welcome to Not Priced In, my asynchronous finance newsletter. This post, and any analysis I’ve offered, is not investing (or life) advice. It is just my personal opinion. I may hold positions in any of the securities discussed. Do your own due diligence. Don’t depend on random newsletters from internet strangers to make portfolio decisions. Subscribe, if you like what you see!

A brief legal tussle ensued when Dewar tried to claim the innovation and the brand for himself, but it ultimately went nowhere.

Of course, it subsequently started protecting its brand name from unauthorised use with a ferocity that would make Velcro blush.

An affiliate marketer gets a small commission every time you order a product from a third party website using their link or code.

I see them everywhere, and I now know why. Thank you. This is priceless writing. ThanQ you for what you have made of this newsletter and your writing.

Perfect timing! Some of us were discussing the Stanley madness with the kids.