I got my first glasses at 13. It wasn’t a surprise – both parents and siblings wore them already, so it was only a matter of time, I thought. Plus, I had a carefully cultivated image of a bookworm, so this felt like the ultimate badge of honour – “I read enough to ruin my eyes!”. Yeah, I was a moron.1

On my first ever visit to an optometrist, I picked a gaudy gold frame, to go with my gold Timex. I’m not sure what the thought process was there, but I’m grateful this was pre-smartphones, and no evidence exists of my Liberace look. Also, props to the optometrist for talking me out of a frame with a gold chain.

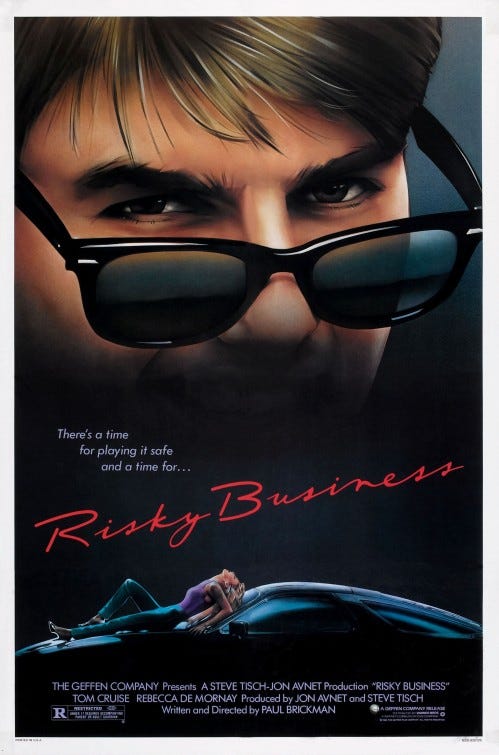

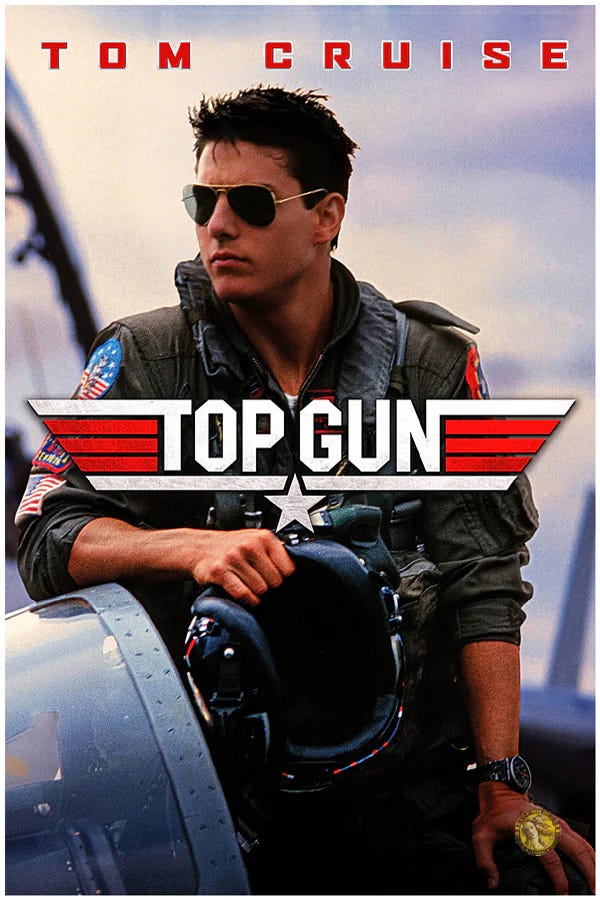

The frame and glasses were quite heavy. This was both due to the frame being metal and the glasses being actual glasses, the kind that could shatter if dropped. We’ve come a long, long way since. The last pair I bought2 was a state-of-the-art Ray-Ban frame with top-of-the-line Crizal lenses – anti reflective, scratch resistant, the works. They cost a bomb too. I justified the purchase because I wore glasses practically every waking moment. Plus, they were Ray Bans. And Tom Cruise wore Ray Bans – aviators in Top Gun, sure. But more importantly Wayfarers in Risky Business.

Turns out, Ray Bans have quite a history. Bausch & Lomb, a pair of German immigrants, started their eponymous company in Rochester, New York in 1853. Beginning with monocles, they eventually covered the entire spectrum - eyeglasses, telescopes, binoculars, and microscopes. One of their early innovations was a pair of spectacles made from Vulcanite, a form of treated rubber. This took off spectacularly during the Civil War, when the steep prices of gold and animal horn made those materials impractical for glasses.

In 1902, William, the second generation Bausch, developed a process to form the lens shape directly by casting molten glass. This was a huge improvement and brought massive savings in production costs and manufacturing times. Previously, the glass parts for the lenses had to be separated, ground and polished in a complicated process.

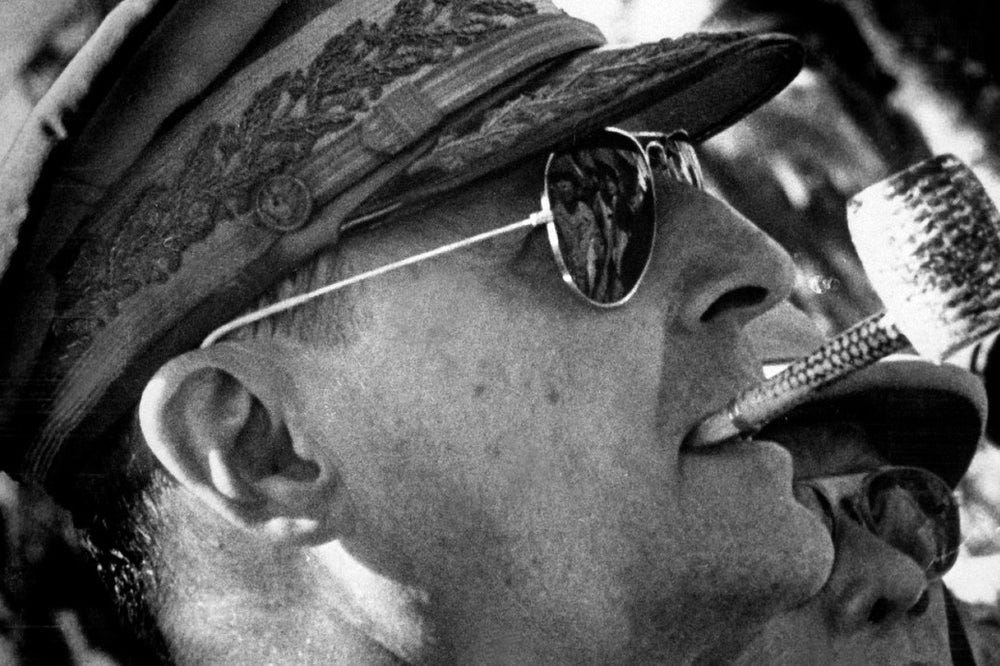

No surprise then, that when military pilots complained of extreme glare at high altitudes, Bausch & Lomb was called in. The first prototype, called “Anti-Glare” was developed in 1936. The teardrop style was designed to provided the maximum coverage and an unrestricted field of vision. The lenses were made from green glass to reduce glare. The final product was christened Ray Ban. The world got their first glimpse of the icon when a photo was published of General Douglas Mac Arthur wearing them while on Leyte Islands, Philippines, in 1944.

The Wayfarers debuted in 1952. They were an instant classic, sported by folks like James Dean and Buddy Holly. Even though they featured prominently in 1980’s The Blues Brothers, sales were declining at an alarming rate, with the entire line verging on extinction – only 18000 pairs sold that year. In 1982, thankfully, Bausch & Lomb signed a $50000 a year deal to get their products placed in movies and TV shows. That’s why Tom Cruise is rocking those wayfarers in Risky Business.

This Hail Mary worked, and 1983 sales was around 360,000 pairs. The company stuck to the strategy, with the now iconic design featuring prominently in The Breakfast Club (1985), along with popular shows like Miami Vice. Sales kept multiplying with each new iconic show and movie that gave a new halo to Ray Bans.

And then came Top Gun (1986) and turbocharged aviator sales- taking the total sales to 1.5 million units. Ray Bans were etched in the public memory forever.

While Ray Ban’s fortunes were waxing and waning, a curious story was developing in Italy. Leonarda Del Vecchio was born in Milan, Italy in 1935. His father, a roadside vegetable vendor, died before he was born. He had four elder siblings, and his mother had to put him in an orphanage. He started work as a metal engraver at age 14, and went on to become an apprentice to a tool and die maker.

At 25, he opened a workshop in the mountainside town of Agordo. The only source of employment, an old mine, had shut. The town council was giving away land to companies willing to relocate there. Del Vecchio took his chance – he asked for 3000 square metres by the riverbank to build a factory. He was going to make parts for spectacles. He built his house next door, and would often start work at 3 am. This was 1961.

Over the next decade, Del Vecchio brought more and more of the spectacle assembly process under his roof, until he was soon assembling entire pairs for his clients. By 1967, he was making his own line of spectacles, which bore the company name – Luxottica. This venture was successful enough that by 1971, he was able to discontinue contract manufacturing entirely – he would only make and sell Luxottica products from now on.

1974 was probably the most pivotal year for the company. It made its first acquisition that year – Scarrone, a well-established wholesale distributor of spectacles in Italy. The eyewear industry back then was both highly fragmented and not very competitive. Margins at every level from the manufacturer to the retailer were eye popping.

Globally, the eyewear industry walked a fine line – medical adjacent, but not quite mainstream. In fact, the first optometry course in the US was taught in Columbia’s Physics department – the medical school refused to play ball. The optical industry embraced the trusted “medical” image that the larger public had. Advertising was generally frowned upon. In Britain, it was actually illegal to display prices of glasses. This meant that opticians could charge whatever they thought they could get away with. This culture pervaded every step of the spectacle supply chain and manufacturing process, fattening margins and encouraging gouging.

Del Vecchio knew the eyewear industry could be vertically integrated easily. Every extra layer that he was able to lop off between himself and the end customer added a significant chunk of margin to his bottom line. More importantly, it gave him control, pricing power, and instant customer feedback. Financing buyouts was also not an issue. The acquisition would start throwing off free cash flows immediately, and the added synergies meant that the bigger he grew, the more margins would accrue. He went on buying smaller manufacturers and other less visible parts of the optical supply chain.

Simultaneously, he pursued international expansion, with new subsidiaries and joint ventures in important markets. In Germany, for instance, the company acquired 9 out of 12 largest distributors in the country, also taking significant stakes in the rest.

The focus was on distribution. This was important for the next part.

Del Vecchio’s second stroke of genius came in 1988, changing the eyewear industry forever. He signed a licensing agreement with his Italian compatriot, Giorgio Armani. Luxottica would make eyewear under the uber-cool and highly aspirational Armani brand name. Until then, glasses were a means to overcome a disability. Even sunglasses, cool as they were, served a purpose. But now they were fashionable. The high priest of fashion had deemed it so3. Glasses were a must have accessory now – no less important than shoes or handbags. Sales went through the roof.

In 1990, he acquired his first big brand – Vogue eyewear. The same year, the company was listed on the New York stock exchange. This was a calculated move – Del Vecchio needed funds for what was to come next. In 1995, he acquired US Shoe in a hostile takeover. It was a spectacular battle – US Shoe was five time bigger, and had a hostile board. But Del Vecchio didn’t back down. He closed the deal for $1.4B, and immediately went about breaking up the 100+ year old company. All he retained was what he was really after – the LensCrafters chain of optical stores. Del Vecchio had finally entered the retail space himself. For the first time in history, a single company could make glasses, offer them under a wide variety of brand names and styles, and sell them to you in its own stores, nationwide.

And then, in 1999, he bought Ray Ban from Bausch & Lomb, for the princely sum of $640m. By now, Ray Ban was a shadow of its former self. Watered down in quality and positioning, it was little more than a cheap gas station brand. During negotiations, Del Vecchio promised to protect jobs at the brand’s four factories in the US and Ireland. Three months after the deal closed, all four plants were shut and production was moved to Italy and China. Over the next couple of years, the brand withdrew from thousands of outlets, hiked prices and improved quality.

In February 2001, he acquired Sunglass Hut For $653m.

In 2004, Del Vecchio decreed that Ray Ban would also sell spectacles. This was absurd – the whole premise and identity of Ray Bans was to, well, ban rays. But yet again, he was right. The market loved this move- and it made Ray Ban the most valuable optical brand in the world.

Del Vecchio had perfected his formula – the more of the supply chain and market you own, the more powerful you get. Soon, 80% of the brands in its stores were made by Luxottica. Now it was time to flex some of this newly acquired muscle.

But let’s take a little detour.

In 1975, Jim Jannard started a company in his garage with the princely sum of $300. His first product was a bike grip:

It is designed as a superior alternative to the basic grip that a regular motorcycle comes with. It is used by motocross and supercross riders, who have more extreme and mission critical requirements from their grips.

Jim named the brand Oakley. Over the next few years, Oakley dominated this niche space, innovating and pushing the boundary on what they could make out of Unobtanium (what they called their proprietary resin) and the injection moulding process.

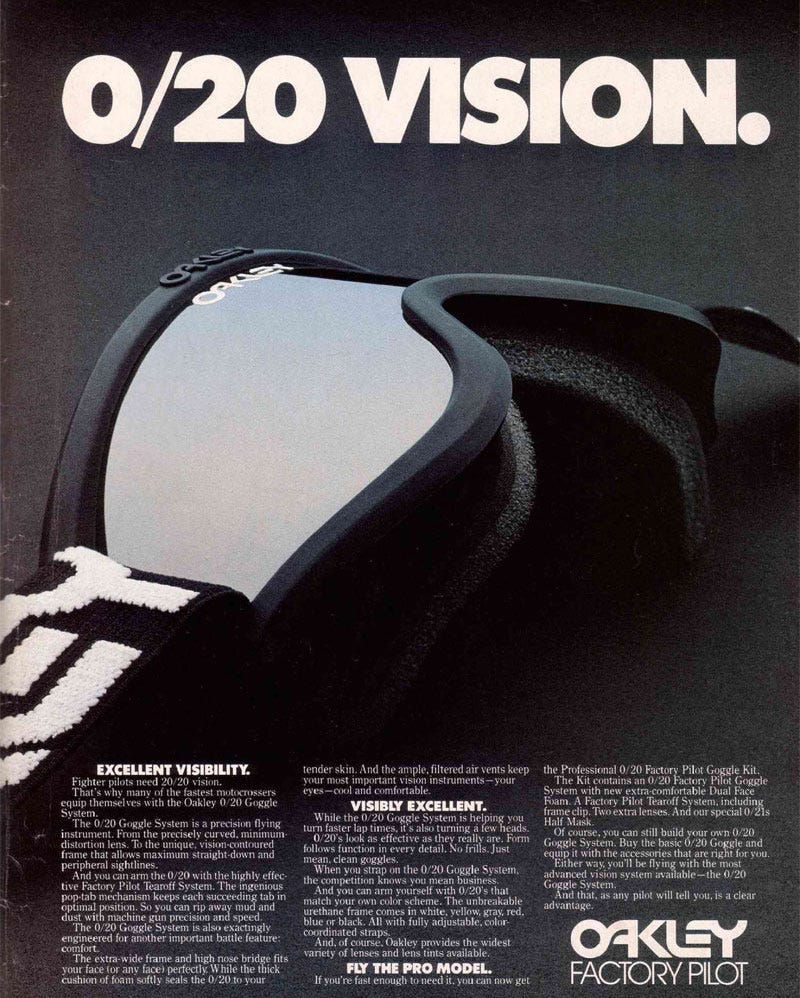

In 1980, Oakley released their first new product – a pair of goggles. With the large Oakley branding on the strap, they were instantly recognisable.

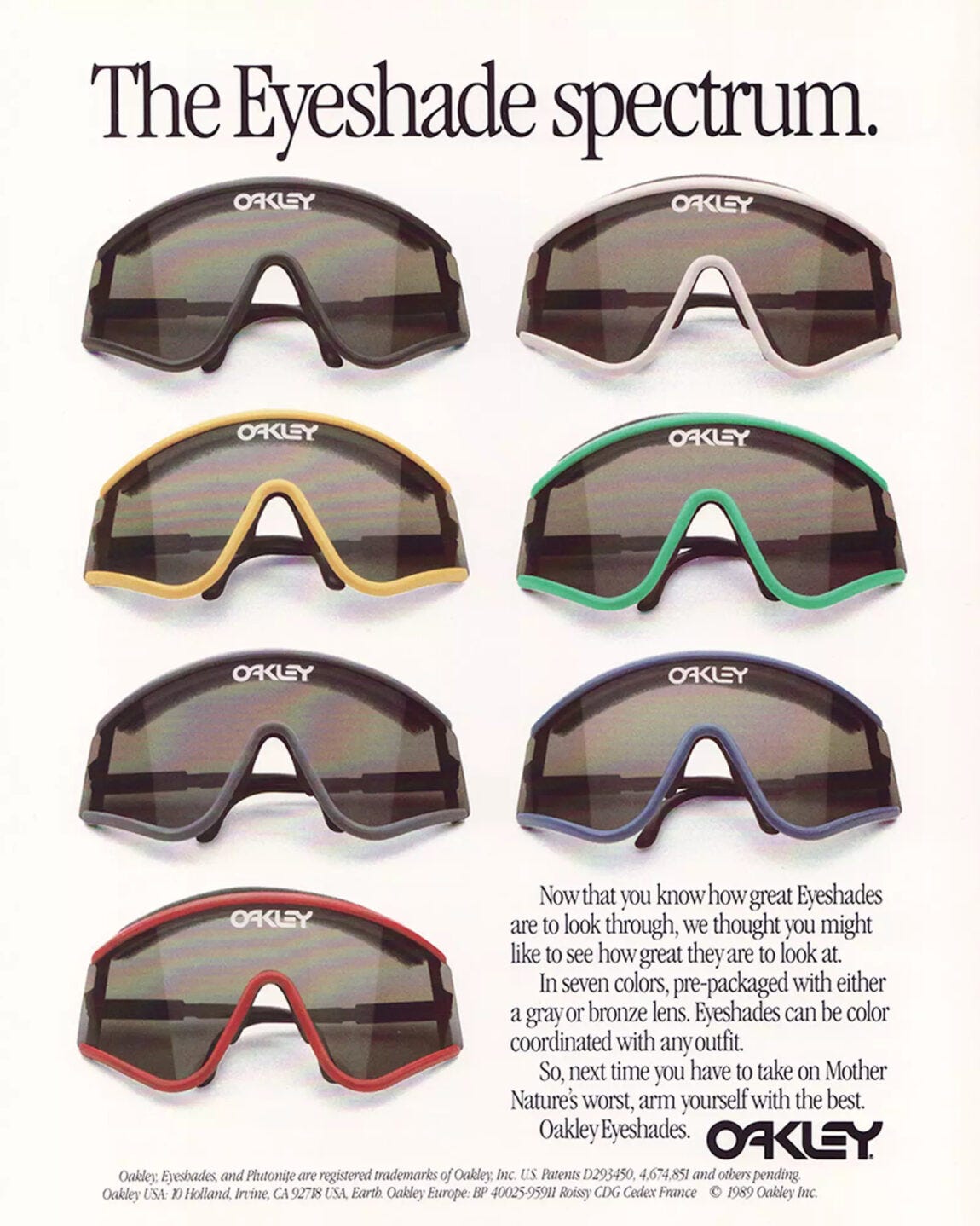

Its first sunglasses followed in 1984 – the Factory Pilot Eyeshades. This was their first mainstream consumer product.

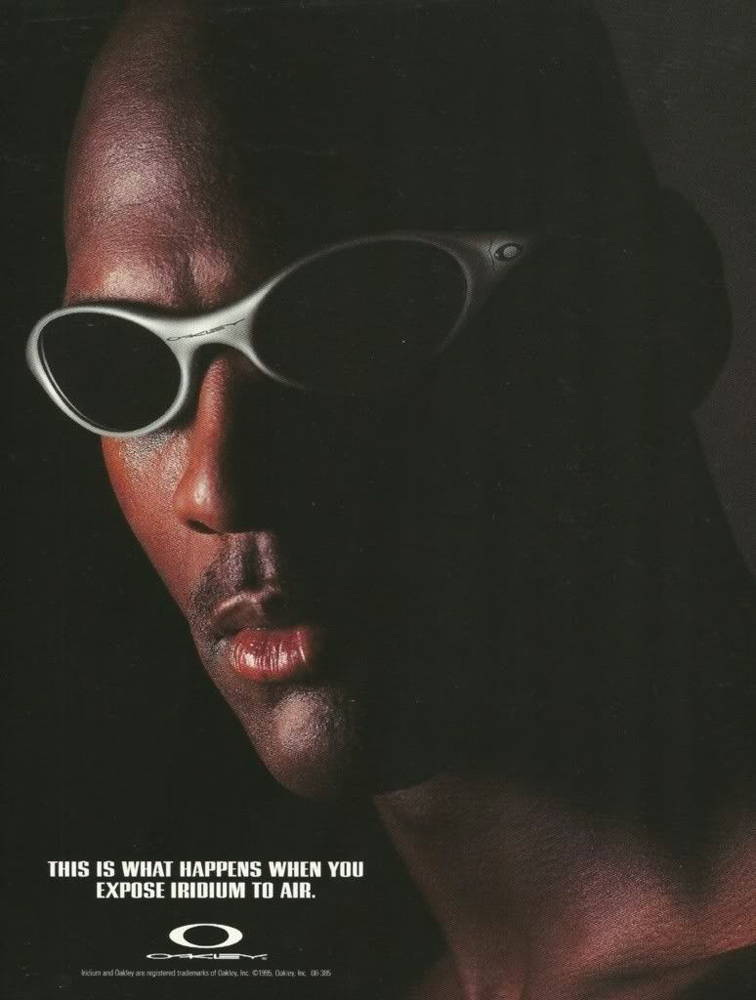

Oakley’s designs were different and fresh, and it had emerged from an authentic subculture. This gave it instant cachet. The company went public in 1995. It kept the growth momentum going for the next decade – featuring many celebrities in its now iconic ads.

In the 2000’s Oakley went on an acquisition spree of its own, starting with Lacon Inc, a chain of sunglasses stores. Around the same time, the company signed a manufacturing deal with Fox Racing. All this while, James was buying back shares of Oakley from the open market, eventually owning over 60% of the company by 2006. In 2007, Oakley bought Oliver Peoples Group for over $50m. James knew that the optical industry was eat or be eaten. All these moves were calculated to fortify himself against the incoming tsunami. Because Del Vecchio was circling overhead.

In the guise of routine negotiations, Luxottica lowballed Oakley on margins. Oakley responded by withdrawing their product from Luxottica stores, including Sunglass Hut. The problem was that this contributed a large chunk of Oakley’s sales. The market reacted immediately, and Oakley’s share price tanked. James could see the writing on the wall – Del Vecchio was not going to let up, even if it meant killing Oakley. He relented, and Luxottica acquired Oakley in 2007 for $2B.

What driving force led a small manufacturer from Italy to become the undisputed King and Emperor of an entire global industry? Here’s a quote from Luigi Francavilla, then Luxottica’s deputy chairman:

“L’appetito cresce con il mangiare,”

(The appetite grows with eating)

Curiously, around the same time that Del Vecchio was starting out, the US Department of Justice uncovered a kickback scheme – Bausch & Lomb and the American Optical Company were paying out some $35m a year (in 1966!) to ophthalmologists to prescribe their lenses. The two companies were banned from opening new wholesale or retail operations for the next 20 years.

This paved the way for Essilor. A French company, Essilor had entered the US in 1972 on the back of their innovative “Varilux” technology – the world’s first progressive lens. Similarly acquisitive, Essilor rolled up the technical “lens” side of the industry: labs, lens manufacturers, instrument makers and D2C websites. Like Luxottica, Essilor didn’t shy away from using its muscle either. Essilor uses so-called “spiff money” – offering stores large, multi-year discounts and cash bonuses for selling its products – in order to squeeze out the competition (Zeiss and Hoya). Soon, it was #2 in global sales, just behind Luxottica.

Imagine the world’s surprise when, in 2014, Del Vecchio came back from a 10-year retirement. With mortality looming, he had one last play left – the merger of Essilor and Luxottica. Announced in January 2017, the combined entity would sell more than a billion pairs every year, and control an estimated 20% global market share. Although its influence extends far beyond what that number suggests.

The company now partners with Meta for its range of smart glasses. In July 2024 it bought Supreme, the street wear brand. In the same month, it also bought an 80% stake in Heidelberg Engineering, which specialises in ophthalmic diagnostic instruments.

Del Vecchio passed in June 2022. The behemoth he built will continue impacting our lives for decades, if not more.

With increased screen time, it is a product that more and more of us are going to need in the decades to come. Meanwhile, churn in the optical industry continues, with luxury conglomerates acquiring brands, direct-to-consumer businesses being built and listed, and acquisitions continue unabated. Will the upstarts topple the behemoth? Can EssilorLuxottica continue the same relentless hunger without Del Vecchio? Remains to be seen.

Welcome to Not Priced In, my irregular finance newsletter. This post, and any analysis I’ve offered, is not investing (or life) advice. It is just my personal opinion. I may hold positions in any of the securities discussed. Do your own due diligence. Don’t depend on random newsletters from internet strangers to make portfolio decisions. Subscribe, if you like what you see!

Still am. But was, too.

I’ve since undergone LASIK, as my perpetually dry eyes will attest.

Armani even took a 5% stake in Luxottica.

Uff, this is like the Illiad of sunglasses. The drama, the intrigue, the corporate bloodbath. Epic stuff, Nitesh!

And I *loved* all the little jokes you sprinked into the narrative.

This post is terrific. You managed to navigate through all those twists and turns without confusing the reader. Wonderful 👏🏽